Books examined

- St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 391 Antiphonarium officii

- St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 375 Gradual

- Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 121(1151) Graduale – Notkeri Sequentiae

Menu

Introduction and background

These three books are collections of chants with music notation produced as aids to support the monastic music practises of two Carolingian monasteries north of the Alps. Two manuscripts were produced by monks from St. Gallen Abbey and the other by those from neighbouring Einsiedeln Abbey. Dating from the mid 10th century to the early 12th century, they are excellent examples of early music manuscripts that reflect the culture and innovation of St. Gallen Abbey. Each book uses the music notation style and system developed at St. Gall (Kelly, 2018), two books include the chants written by the prominent St. Gall monk Notker Balbulus (Cod. Sang. 375 and Codex 121), and one book was produced entirely by renowned scribe and music notation expert, Harker of St. Gallen (Cod. Sang. 391) (Fassler, 2018; Hartker von St. Gallen, 2021).

The books house chants sung during the Mass and at the service of the Devine Office, specifically collections of chants in the Gradual, Sequentiary, and Antiphoner forms. The chants include those sung in unison by a group of monks, by a solo singer, and by a soloist and group in a call and response style, as in the responsorial gradual chants (McKinnon, 2001)

music notation supported an existing oral tradition of chanting

At the time of these books’ production and use, music notation supported an existing oral tradition of chanting (Treitler, 2007, pp. 238–239). No abrupt change happened in medieval Europe where the written musical culture supplanted an oral one; thus, these early notated books are part of a “transitional period in chant performance, where the oral tradition was guided by writing but not dependant on it” (Karp, 1998 in Helsen, 2008, pp. 23–24). One way music books could support this transition was as a control, a type of reference book that would be consulted to check whether chants had been remembered correctly (Roesner, 1993, p. 754; Treitler, 2007, pp. 249–250), and were being performed with the proper musical nuances in relationship with the text (Kelly, 2018, p. 245; Rankin, 2011).

Cantors, or other monastic music and liturgical experts, most likely used these books as reference sources. Tasked with making sure lectors and singers could perform their assigned liturgical duties properly, cantors and other experts needed to find and review the appropriate chants and pass musical knowledge onto the monastic community (Bugyis et al., 2017, pp. 2-3; Kelly, 2018, p. 245).This was no easy task considering the vast number of chants in the Gregorian repertory in use by the 10th century in monasteries such as St. Gallen and Einsiedeln. The number is estimated to be over 2500, which totals approximately 80 hours of music (Helsen, 2008, p. 282). As aids to memory then, music manuscripts helped cantors and other experts with managing the monastic music and chants and their practice.

Those consulting these collections of chants had different information needs depending on the level of musical and liturgical knowledge of the monks they taught, how well they knew specific chants themselves, what level of performance was expected for a given service, and so on (Boynton, 2003, p. 155). So, the daily purposes for consulting these books would vary.

the oral music and liturgical practise of a monastery formally displayed in a visual medium

Last, books of collections of chants written with music notation were also sometimes used to formally display in a visual medium the oral music and liturgical practise of a monastery (Hild, 2014, p. iii). As well, decorated and meticulously copied music manuscripts may have been used not only as reference books, but as means to visually display a record of the liturgy with reverence (Roesner, 1993, p. 754).

Compare and contrast

Two of the books have a moderate size, Cod. Sang. 391 is 215 x 165 mm and Cod. Sang. 375 is slightly narrower at 214 x 156 mm. Codex 121 is smaller, but not tiny, at 160 x 105 mm. They range from 264 pages to 332 pages. These dimensions are not dissimilar to a thick paperback book of today and could be held or carried around without trouble. None of the books have original bindings and Cod. Sang. 391 is only one half of an original manuscript, the Hartker Antiphonary. Each displays considerable wear, such as dark patches and staining (Cod. Sang. 375 p. 79, Codex 121 p. 29). As well, Cod. Sang. 391 includes many additions from later centuries (see e-codices description). Most of the pages of each book include music notation, in St. Gallen neumes, meticulously written in expert hands.

IDENTIFICATION AIDS

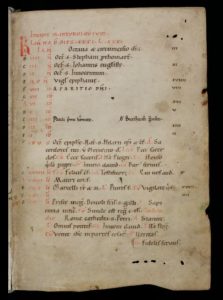

The books in their present condition do not appear to share similar aids, which help the user identify the books’ contents. The first pages of Codex 121 are missing, so an identification aid such as a title page or list of primary chants may have been lost. The scribe of Cod. Sang. 391 began with a list of the antiphons contained in the book, which gives a user a snapshot of the books’ contents (pp. 1-8). At the start of Cod. Sang. 375, a calendar lists the most important St. Gallen saints’ festivals, which similarly gives the user an idea of the text’s contents (pp. 3-21). As well, a rubricated title “incipit gradualis liber” introduces the gradual section that follows (p. 23).

FINDING AIDS

The scribes did not add page numbers during the production of the three books. Besides no page numbers, the books lack running titles, and two books (Cod. Sang 375 and Cod, 121) have no subject index or table of contents. The scribe of Cod. Sang. 391 has included an ordered list of all the antiphons under rubricated headings at the start (Cod. Sang. 391, pp. 1-8) as well as an index of antiphons at the back of the book (Cod. Sang. 391, pp. 261-264) to direct readers to chants they need. In all three books, the scribes have introduced each section with an initial. These initials aid the user in finding the start of each chant, sections of the liturgical text, or grouping of chants.

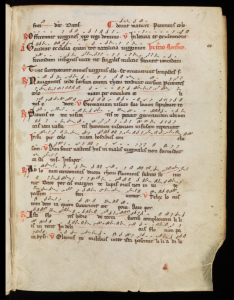

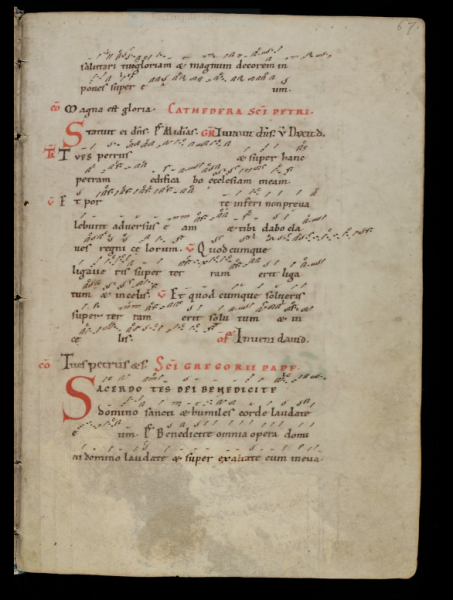

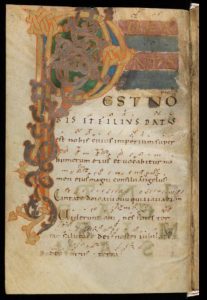

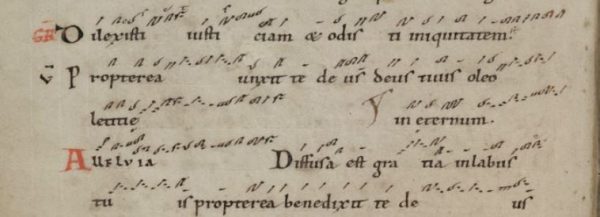

In order to help users find chants they need more quickly as they turn and scan the books’ pages, the scribes have also used initials at three (Cod. Sang. 375, Codex 121) and two (Cod. Sang. 391) hierarchy levels. In Cod. Sang. 375 the two main sections of the book, the Gradual and the Sequentiar, are introduced with a large, elaborately decorated initial (Cod. Sang. 375 p. 23 and p. 237) . These initials are decorated with a floral and vine design painted with a neat and skilled hand with details in red paint and filled in with painted washes in blue, green, and transparent tan paint.

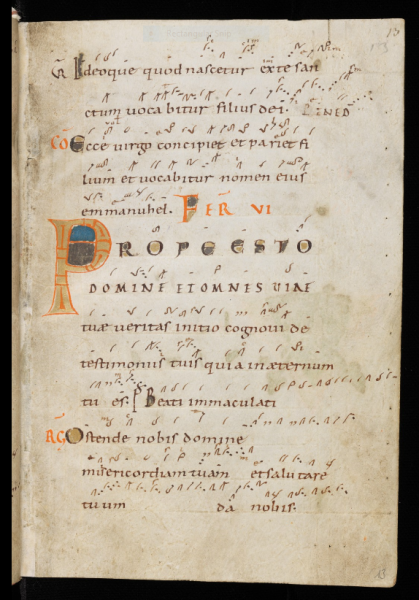

The scribe of Codex 121 deployed even larger elaborate and colourful initials to demarcate the book’s main sections (p. 30). This scribe’s secondary initials, introducing each grouping of chants, are similarly painted with a neat and skilled hand. They have red lines, painted floral and vine patterns, and colourful washes, including gold and silver pigments (p. 26)—sharing design features with the large, primary-level initials of Cod. Sang. 375 as well. Cod. Sang. 391 lacks huge, highly decorated colourful initials but includes an elaborated initial page (p. 34) and one initial (p. 201) of ornate penwork in red ink with wickerwork patterns. To introduce chants, the scribes of both Cod. Sang. 391 and Cod. Sang 375 included similar initials neatly painted in red ink with regular letter shapes at heights around 2-3 lines (Cod. Sang 391, p. 58), and some with simple decorative flourishes (Cod. Sang. 375, p. 27) as well as a few with the same multi-coloured style of the larger initials to help users distinguish and find the chants for more important feast days of the liturgical year (St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 375: Gradual, n.d.).

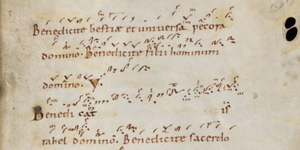

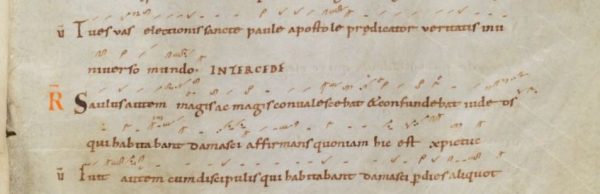

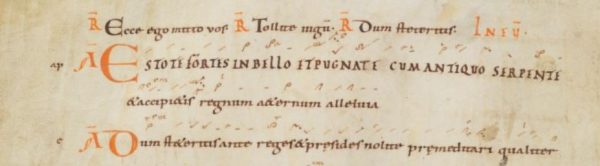

Headings rubricated in red ink are used in all three books. These headings could help a user quickly find and identify which chants correspond to which sections of the Mass, days of the liturgical calendar, psalms, or other liturgical groupings. These headings are neatly drawn in all capital letters in a Rustic style (e.g., Cod. Sang. 391, p. 166). Other information about each chant’s smaller units is communicated to the user with rubricated abbreviations preceding the start of lines in the left margin or within the text block (Codex 121, p. 296, Cod. Sang. 375 p. 229).

AIDS TO ENHANCE CLARITY

Because the primary purpose of these books was to support the music practises of chanting at the monasteries, adding aids to clarify the meaning of the text in the books did not seem to be prioritized during book production. There are no aids to enhance the clarity of music information provided through the music notation. For example, no key to help understand the specialized symbols in the notation. Some of the marginal letters in each book, however, may be keys to help the user determine a chant’s mode. For example, Joseph Dyer identifies the letters a e i o u y η ω as indicating the mode of chants in Cod. Sang. 391 (p. 93 “u”) (Dyer, 2018, p. 109).

STRUCTURING AIDS

In all three books, the scribes have helped the user find what level they were at in the book by deploying a hierarchy for initials (as described earlier) and a simple script hierarchy (all-caps for a chant’s first line following the initial). For example, the initials placed at the start of a grouping of chants help the user recognize these sections when turning pages and scanning for a particular chant. The scribe of Codex 121 added one more level to this structure by continuing the capital letters for two lines and writing the first line in larger letters, decorating them with washes of gold and silver paint. Each book’s script hierarchy demarcates each chant’s first line by writing them in all capital letters. The first letter of chant lines that come at the start of a ruled line projects into the margin (Gumbert, 1993, p. 10). Rubricated abbreviations at the start of lines help the user follow the chants’ structure and communicate performance practice information. For example, in the sections of the books containing antiphons or graduals, the alternating verses (sung by a soloist) and responses (sung by the community of monks) are indicated with A and R, respectively (e.g. Cod. 391, p 166) and perhaps by other abbreviations used in Cod. Sang. 375. As well, the contrast between the black/brown ink used for text and notation to be sung with the red ink for rubrics, helped the reader quickly recognize these different information layers.

Full page, detailed illustrations are also used in two books to help the user identify sections of the book. The Sequentory section of Cod. Sang. 375 is preceded by a colourful, expertly drawn and painted Christmas scene on page (p. 236). The illustrator of Cod. Sang. 391 has drawn with equal skill coloured pen illustrations depicting biblical scenes corresponding to the antiphons for periods in the liturgical calendar (the illustrator, Hartker, was also the scribe) (St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 391: Antiphonarium Officii’). For example, chants for Easter are introduced with a Crucifixion scene (p. 27) and then an Easter scene.

The scribes of each book chose the page design type T of one column of text with margins. For most sections of all the books, the scribes ruled the pages to have lines with enough space between them to accommodate the chant text with notation above it. (Rankin, 2018) This page design allows enough space to fit in the music notation, which requires vertical space for showing differences in pitches, while still appearing orderly, so as not to disorient the reader.

The scribes have also applied a notation system very consistently with notes written above the syllable of text to which they are tied (Kelly, 2018, pp. 239–240). This clear structure helps the user keep straight which notes should be sung with which syllables. This structure is easy to see where a melisma (an extended grouping of notes) is tied to one syllable of text, so a gap in the text is noticeable (Cod. Sang. 375 p. 26, Codex 121 p. 102). On those pages, there are also examples of melismas that come at syllables at the ends of a text line. In these cases, the music notation continues into the right margin (also seen here, Cod. Sang. 391 p. 184, but with shorter melismas).

Why the similarities?

First, the books’ page design was suitable for displaying text and notation. A type T page design with lines ruled for text with notation above is consistently used, making up the bulk of all three books. A single column of text and music lines allows the reader to follow the line of chant more easily than if the lines were broken into two columns. This single column is necessary because the reader must read both text and music simultaneously. This characteristic of reading music with text would make breaking lines disorienting, especially when melismas were broken partway through.

The line ruling used in the books’ page design provides enough space for the music notation to sit above text. The space between lines is sufficient to display the contours of melody, symbols for performance indicators, and other neumes, to fit and be legible ( See Roesner, p. 754, for a description of the wealth of nuance and detail in the notation in Codex 121). Without legible music notation, these music books would be ineffective reference tools for supporting and controlling a monastery’s oral chant performance practice. Overall, the pages in these three books appear uncluttered with few distracting features. For a cantor, or other music expert, to become more familiar with, recollect, or confirm a chant’s structural patterns and musical features, the music notation must be unobstructed and clear.

The line ruling used in the books’ page design provides enough space for the music notation to sit above text. The space between lines is sufficient to display the contours of melody, symbols for performance indicators, and other neumes, to fit and be legible ( See Roesner, p. 754, for a description of the wealth of nuance and detail in the notation in Codex 121). Without legible music notation, these music books would be ineffective reference tools for supporting and controlling a monastery’s oral chant performance practice. Overall, the pages in these three books appear uncluttered with few distracting features. For a cantor, or other music expert, to become more familiar with, recollect, or confirm a chant’s structural patterns and musical features, the music notation must be unobstructed and clear.

The numerous finding aids in the three books—including initials and rubricated headings for chant groupings and individual chants—would be indispensable to those needing to locate chants on a daily basis or in a hurry. The books’ initials help such a user find information at different levels in the book, from the books’ main sections to a specific chant for a particular liturgical observance. Tasked with managing the oral music practice of performing a vast repertory of chants throughout the year, a cantor could take advantage of these finding aids while selecting notated chants for consultation or practise.

While reviewing how to perform a certain chant and memorizing its features, cantors could also benefit from the finding and clarifying aids at a more micro-level, such as marginal letters, a line’s rubricked first letter, or even paragraphus marks. These aids would be helpful tools for efficiently and effectively finding, noticing, and understanding a chants’ features and meta-information and then passing this on to the monastic community. This variety of aids to locate and make sense of the music and textual information on these books’ pages would be useful considering those consulting these collections of chants had different information needs depending on their familiarity with the chants and that of the monks they were helping, and other changing needs.

The structuring aids used in these books—such as the script hierarchy marking a chant’s beginning, rubricated letters delineating chant lines for a soloist and lines for a group of singers, and other performance practise information indicated by abbreviated text—would be essential for making sense of and finding your place in the vast amount and variety of textual and musical information presented in these three books.

The high quality and full-page illustrations and oversized decorated initials do help a user identify book sections, while the numerous smaller decorated initials stand out on a page and direct a user to key information, helping them make sense of the books’ structure. However, these initials and illustrations needn’t be as beautiful and detailed as those in these three books to function in these ways. The high-quality illustrations and decorated initials, although differing in style among the three books, are useful in another way. Produced during a transitional period from an entirely oral tradition of chant performance to a tradition that would become more controlled by written notated music, these decorations are useful in marking these books as important or official. Although used as reference books, as Hild (2014) and Roesner (1993, 754) stated, these music books, and others like them, most likely also functioned to formally display in a visual medium the music and liturgical practices of a monastery. The decorations in these books, then, are useful in communicating the idea that these books, as visual representations of oral culture, are important and valuable as material objects.

References

Boynton, S. (2003). Orality, Literacy, and the Early Notation of the Office Hymns. Journal of the American Musicological Society, 56(1), 99–168. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2003.56.1.99

Bugyis, K. A.-M., Kraebel, A. B., & Fassler, M. E. (2017). Medieval Cantors and their Craft: Music, Liturgy and the Shaping of History, 800-1500.

Dyer, J. (2018). Sources of Romano-Frankish Liturgy and Music. In M. Everist & T. F. Kelly (Eds.), The Cambridge history of medieval music (pp. 92–122). Cambridge University Press.

Fassler, M. (2018). Music and Prosopography. In M. Everist & T. F. Kelly (Eds.), The Cambridge history of medieval music (pp. 176–209). Cambridge University Press.

Gumbert, J. P. (1993). ‘Typography’ in the manuscript book. Journal of the Printing Historical Society, 22, 5–28.

Hartker von St. Gallen. (2021, April 3). Wikipedia. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hartker_von_St._Gallen

Helsen, K. E. (2008). The Great Responsories of the Divine Office: Aspects of structure and transmission [PhD diss]. Universität Regensburg.

Hild, E. S. (2014). Verse, music, and notation: Observations on settings of poetry in Sankt Gallen’s ninth- and tenth-century manuscripts [PhD diss]. University of Colorado at Boulder

Kelly, T. F. (2018). Notation I. In M. Everist & T. F. Kelly (Eds.), The Cambridge history of medieval music (pp. 236–262). Cambridge University Press.

McKinnon, J. W. (2001). Gradual. New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11576

Rankin, S. (2011). On the treatment of pitch in early music writing. Early Music History, 30, 105–175. Cambridge Core. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261127911000039

Rankin, S. (2018). Writing Sounds in Carolingian Europe: The Invention of Musical Notation (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108368605

Roesner, E. H. (1993). Music Reviews: Facsimilies—"Codex 121 Einsiedeln: Graduale und Sequenzen Notkers von St. Gallen"; ‘Codex 121 Einsiedeln: Kommentar zum Faksimile’ Hrsg. Von Otto Lang mit Beitragen von Gunilla Bjorkvall, Johannes Duft, Anton von Euw, Rupert Fischer, Andreas Haug, Ritva Jacobsson, Godehard Joppich und Odo Lang. Notes - Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association, 50(2), 751–756.

St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 375: Gradual. (n.d.). E-Codices. https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0375/

St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 391:Antiphonarium officii. (n.d.). E-Codices. https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0391

Treitler, L. (2007). With Voice and Pen: Coming to Know Medieval Song and How it Was Made. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199214761.001.0001